Early Onset Of Summer Could Create Hardships For Agro-Based Indian Factories

Since the last 50 years, Nitin Goel’s family’s clothing business in the Indian textile city of Ludhiana is involved in the making of jackets, sweaters and other woollen apparels. However, the company fears its own set of challenges with a relatively early onset of summer. Goel states that they have started making t-shirts instead of sweaters as the winter is getting shorter with each passing year. Moreover, their sales have halved in the last five years and are down a further 10% during the current season. The only recent exception, he says, was the Covid, when temperatures dropped significantly.

As winter is all set to bid farewell across the country, agricultural and buisness models apprehend changes. Winter clothes manufacturers cite rising temperatures as the reason of retail clients showing hesitation to accept even confirmed orders. As per data from the Indian Meteorological Department, this year’s February was India’s hottest in 125 years. Additionally, the weekly average minimum temperature was above normal by 1-3C in many parts of the country. The weather agency has issued a warning stating that above-normal maximum temperatures, alongwith heatwaves, are likely to persist between March and May in most parts of the country. Such inconsistent weather brings serious problems for Goel, who has been involved in small scale buisness. In addition to low sales, he has had to face the risk of his buisness model getting changed.

Across India, multi-brand outlets get their supply of clothes from Goel’s company. He says that the outlets no longer pay him when the goods get delivered. He adds that they have adopted a “sale or return” model, wherein consignments that remain unsold are returned to the company, which entirely transfers the risk on the manufacturer.

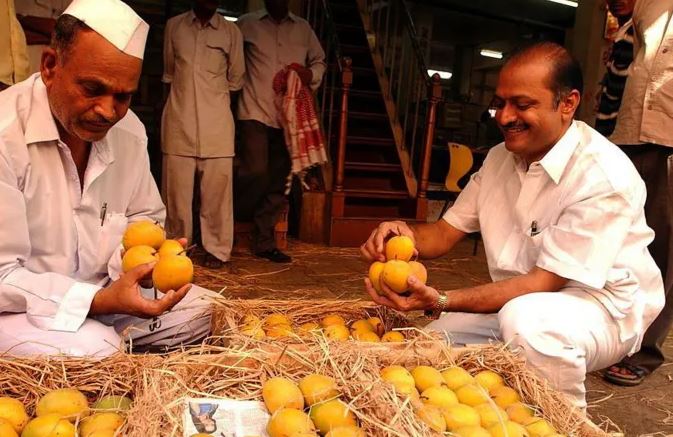

In such situations, he has had to offer bigger discounts and incentives to his clients this year. According to Goel, big retailers have not yet picked up goods despite confirmed orders. Moreover, as a result, some small buisnesses in his town have had to shut down. Yields have reduced at India’s widely popular Alphonso mango orchards, owing to heat, on the country’s western coast.

The Alphonso mango orchards in the town of Devgad on India’s western coast are facing dire consequences due to heat. Vidyadhar Joshi, a farmer who owns 1,500 trees, said that production in the ongoing year would be only around 30% of the normal yield. Although the Alphonso is a highly valuable export from the region, the districts of Raigad, Sindhudurg, and Ratnagiri, where the variety is grown predominantly, the yields are lower, as per Joshi.

He further adds that they might make losses the current year, as he had to spend more resources than usual on irrigation and fertilisers in an attempt to retrieve the crop. Other farmers in the area had started sending labourers, who hailed from Nepal, coming to work in the orchards back home as there wasn’t enough to do.

On the other hand, unbearably hot weather is also threatening winter crops of wheat, rapeseed, and chickpea. At one point where the agriculture minister of the country has disregarded concerns about poor yields and predicted about having a bumper harvest of wheat this year, independent experts in this field see less hope.

Heatwaves in 2022 lowered yields by 15-25% and “similar trends could follow this year”, says Abhishek Jain of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (Ceew) think tank. In case of such disturbances,India will have to rely on expensive imports, and its prolonged ban on exports, announced in 2022, may continue for even longer.

Economists are also worried about the effect of soaring temperatures on availability of water for agricultural purposes. Reservoir levels in northern India have already dropped to 28% of capacity, down from 37% last year, according to Ceew. This could affect fruit and vegetable yields and the dairy sector, which has already experienced a decline in milk production of up to 15% in some parts of the country.

Madan Sabnavis, Chief Economist with Bank of Baroda, claims that these things have the potential to push inflation up and reverse the 4% target that the central bank has been talking about. On a positive note, food prices in India have started softening after being high for several months, in turn leading to rate cuts after a period of stagnation.

GDP in Asia’s third largest economy has also been supported by accelerating rural consumption recently after hitting a seven-quarter low last year. Any setback to this farm-led recovery could affect overall growth, at a time when urban households have been cutting back and private investment hasn’t picked up.

Think tanks like Ceew state that a range of urgent measures to mitigate the impact of recurrent heatwaves needs to be thought through, including better weather forecasting infrastructure, agriculture insurance and evolving cropping calendars with climate models to reduce risks and improve yields.

As a primarily agrarian country, India is particularly and undeniably vulnerable to climate change. Ceew estimates three out of every four Indian districts are “extreme event hotspots” and 40% exhibit what is called “a swapping trend” – which means traditionally flood-prone areas are witnessing more frequent and intense droughts and vice-versa.

The country is expected to lose about 5.8% of daily working hours due to heat stress by 2030, according to one estimate. Climate Transparency, the advocacy group, had pegged India’s potential income loss across services, manufacturing, agriculture and construction sectors from labour capacity reduction due to extreme heat at $159bn in 2021- or 5.4% of its GDP. With an absence of intense and top-priority action, India risks a future where heatwaves threaten and intimidate both lives and economic stability.