In a significant advisory opinion, the Supreme Court of India has empowered state governments to seek judicial intervention against governors who unduly delay assent to bills, drawing praise from legal luminaries and opposition figures. The ruling, delivered by a five-judge bench, addresses longstanding tensions between state executives and gubernatorial discretion, offering a pathway to resolve political gridlocks without imposing rigid deadlines.

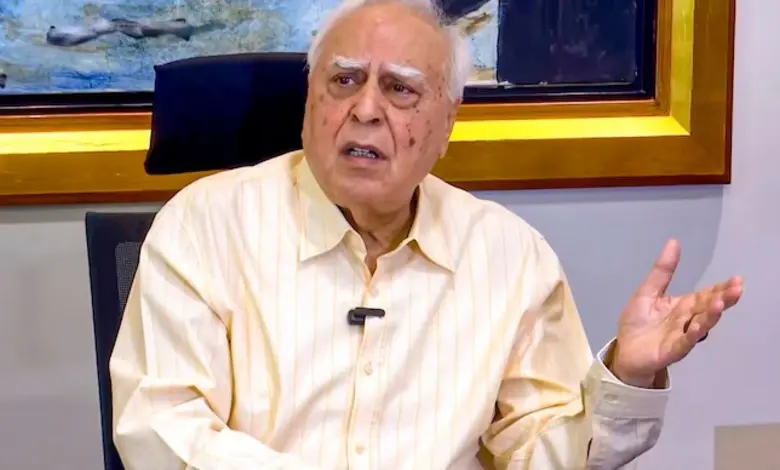

Senior advocate and Rajya Sabha MP Kapil Sibal, who argued on behalf of West Bengal in related proceedings, hailed the development as a “100% win” for federalism during an interview with India Today. Representing states frustrated by what they perceive as politically motivated delays, Sibal emphasized that the opinion effectively limits governors’ options to three—granting assent, withholding it with reasons, or reserving the bill for the president’s consideration—rejecting the Union government’s contention of unlimited veto power.

“The court has constitutionally affirmed that governors cannot indefinitely pocket veto bills,” Sibal explained. He highlighted the flexibility introduced: rather than adhering to the three-month timeline set by a prior two-judge bench of Justices JB Pardiwala and R Mahadevan in the Tamil Nadu case, aggrieved states can now petition the court directly, naming the governor as a respondent. “Imagine a bill languishing for three, four, or even five years—states can now demand accountability in court,” he added, predicting a shift in governors’ conduct to avoid such scrutiny.

The opinion stems from a presidential reference seeking clarity on governors’ roles, following complaints from opposition-ruled states like Tamil Nadu and West Bengal. It overturns the fixed timeline from an earlier April ruling but preserves states’ remedies against “inordinate delay,” as detailed in India Today’s coverage of the bench’s advisory.

Echoing Sibal’s optimism, DMK Rajya Sabha MP and senior lawyer P Wilson, whose party and the Tamil Nadu government intervened in the reference, described the outcome as protective of state prerogatives. “This advisory doesn’t erode our rights; the Supreme Court couldn’t revoke the prior timeline order anyway,” Wilson told India Today. He stressed the ruling’s advisory nature, distinguishing it from binding judgments, yet underscored its practical value: “Governors must operate within constitutional bounds. If they falter on reasonable timelines, states have recourse to the courts.”

Wilson pointed out that the Tamil Nadu governor has already complied with the earlier three-month directive in practice, suggesting the new opinion reinforces rather than resets the status quo. “Call it an opinion, not a verdict—but it arms states against arbitrary holds,” he noted.

Legal experts view this as a balanced recalibration of Article 200, which governs bill assents, curbing potential misuse while upholding the governor’s ceremonial role. As states gear up to test these provisions, the ruling could reshape Centre-state dynamics, ensuring legislative momentum isn’t stifled by executive inertia.