In the lush landscapes of Kerala, a silent killer lurks in warm waters, prompting a statewide vigilance as cases of a rare, lethal infection have surged. Authorities are ramping up surveillance after infections from the notorious “brain-eating amoeba” have doubled year-over-year, with 19 fatalities recorded this year nine of them just in September.

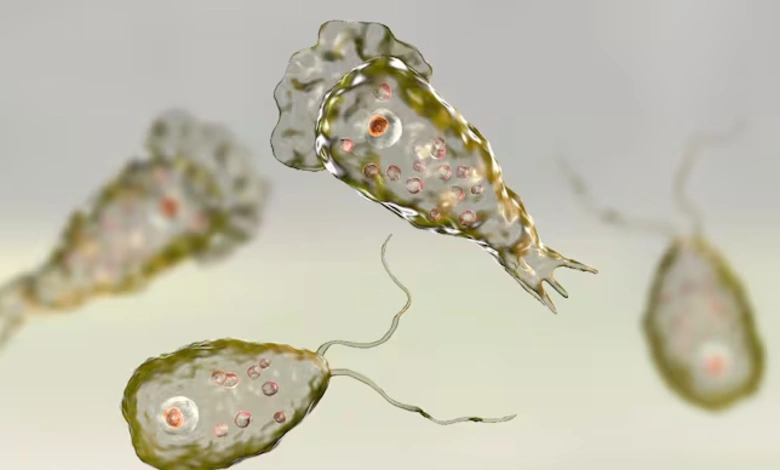

Last year, the southern Indian state grappled with 36 instances of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis, a devastating condition triggered by the Naegleria fowleri amoeba. Dubbed the “brain-eating amoeba” for its ability to invade the brain and ravage neural tissue, it poses a grave threat once it takes hold. This year, the tally stands at 72 infections and those 19 deaths, though health officials emphasize no clustered outbreaks have emerged, unlike the concentrated tragedies of 2024, when nine out of 36 patients succumbed.

Dr. Altaf Ali, a key member of a government task force dedicated to curbing the spread, described the uptick as concerning but manageable. “The numbers remain small, yet we’re scaling up tests statewide to identify and intervene early,” he told the AFP news agency. What alarms experts most is the amoeba’s newfound reach: whereas past incidents were confined to isolated hotspots, 2025’s cases have surfaced across diverse regions, signaling a broader environmental risk.

Kerala’s Health Minister Veena George underscored the distributed nature of the threat, with September alone logging 24 new infections alongside the nine losses. The amoeba, which flourishes in heated freshwater bodies like lakes and rivers, enters the body through the nose during activities such as swimming. It cannot transmit between individuals, but its impact is merciless: if it breaches the brain, mortality exceeds 95%, as noted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The infection is exceptionally uncommon globally yet almost invariably deadly.

Early warning signs, per the World Health Organisation (WHO), include severe headache, fever, and vomiting, escalating swiftly to convulsions, confusion, hallucinations, and coma. Since 1962, around 500 cases have surfaced worldwide, predominantly in the United States, India, Pakistan, and Australia—highlighting a pattern tied to tropical climates.

As Kerala bolsters water quality checks and public awareness campaigns, the outbreak serves as a stark reminder of nature’s hidden perils. Officials urge caution during water-based recreation, advocating nasal clips or boiled water for rinses to avert tragedy in this vulnerable paradise.