At 95, AIIMS’ First Woman Director Reveals Untold Stories of Indira Gandhi, VIP Culture & Anti-Sikh Riots

Dr Sneh Bhargava's new memoir reveals VIP interference, healthcare corruption, and her front-row seat to India's political upheavals during her groundbreaking tenure

(by our correspondent)

Dr Sneh Bhargava began her historic role as AIIMS’ first female director on October 31, 1984, walking into an unprecedented crisis. Within hours of her appointment, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s bullet-riddled body arrived at the hospital’s emergency department, her saffron sari torn by 33 gunshot wounds.

In her recently published memoir “The Woman Who Ran AIIMS” by Juggernaut, Bhargava describes the traumatic scene: “The cold metal of the gurney against the skin would have made any patient wince.”

The situation was chaotic. Sonia Gandhi, Gandhi’s daughter-in-law, could barely manage to say “She has been shot” before fainting from shock. Senior medical staff worked frantically as bullets “tumbled out and clattered to the floor,” though any chance of survival had already passed. “She had no pulse,” Bhargava remembered. The desperate search for Gandhi’s rare B-negative blood type quickly exhausted supplies, forcing doctors to use O-negative reserves while a Sikh technician operating critical equipment abandoned his post, terrified of potential mob violence.

Despite Gandhi being clinically dead upon arrival, Bhargava was instructed to maintain a four-hour deception to prevent governmental chaos while President Zail Singh was overseas and Rajiv Gandhi was campaigning. “Our job… was to keep up the charade that we were trying to save her life, when in fact she was dead when she was brought to AIIMS,” she documented.

Protecting Staff During Anti-Sikh Violence

As anti-Sikh riots erupted across the city, claiming thousands of lives, Bhargava arranged police protection for Sikh employees and converted her residence into a safe haven. She witnessed the riot’s brutal aftermath firsthand: “Many of the injured were brought to AIIMS with burns caused by being doused with petrol and set alight” – a horrifying reminder of the violence that challenged her early leadership.

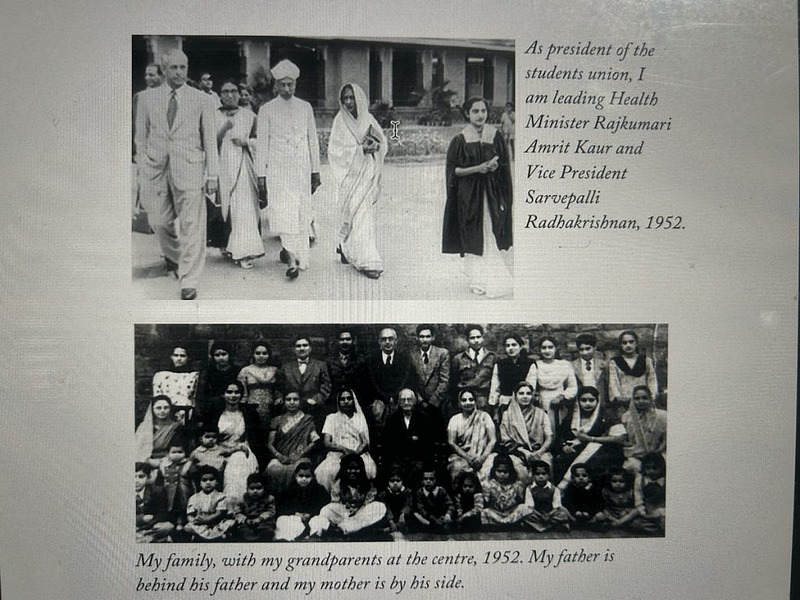

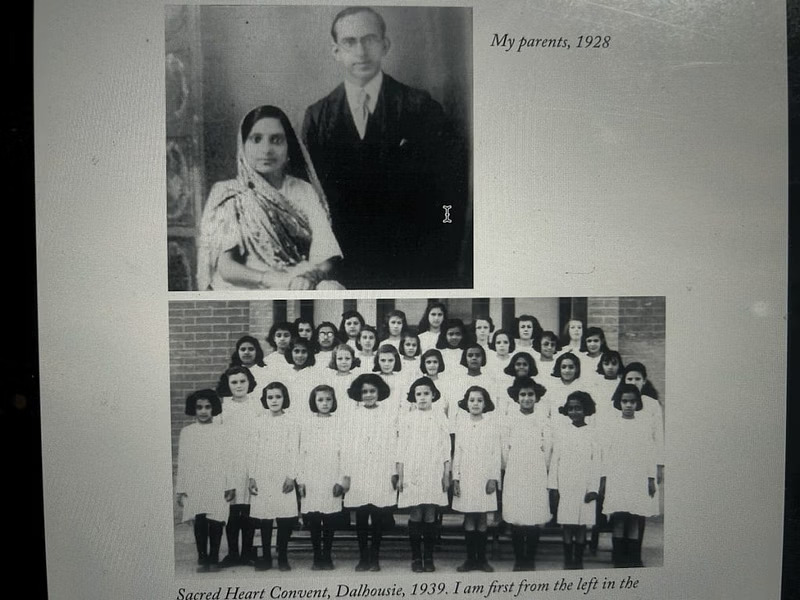

Bhargava’s path to AIIMS leadership was fraught with gender-based skepticism. Despite Indira Gandhi’s appointment, she encountered sexist doubt that “a woman could not possibly handle the task.” Following the assassination, critics predicted her failure, with colleagues warning: “You’ve missed your chance… they’ll lobby hard to stop you.” However, Rajiv Gandhi validated her position upon assuming office. “In my time as director, I had the privilege of interacting with two prime ministers… before handing over the reins,” she reflected.

Confronting Political Interference

Her directorship became a constant battle against political meddling. When a Member of Parliament’s family illegally occupied an AIIMS apartment, Bhargava ordered their removal. The politician threatened: “I will shake the walls of the institute if you evict my kin.” Her response was unwavering: “The walls of AIIMS and my shoulders are not that weak. You’re on the wrong side of the rules.”

Bhargava’s encounters with political VIPs began years before her directorship. As a junior radiologist in 1962, she prepared a barium solution for Jawaharlal Nehru’s chest examination, only to watch security discard it and demand a fresh preparation under their supervision. The scan revealed a dangerous aortic aneurysm – essentially a fatal time bomb.

When Nehru died in 1964 from aortic rupture, Bhargava grimly noted: “My initial diagnosis had been correct.” A subsequent 1963 examination became a disaster when seniors overruled her suggestion to use experienced AIIMS personnel, instead bringing outsiders whose incompetent injections left Nehru’s arms “blue, purple, and angry.” He departed wearing full sleeves to conceal the bruising. Dr KL Wig later admitted in his memoir: “I chose the wrong person… many good ones were available.”

Rajiv Gandhi’s Risky Hospital Visits

Rajiv Gandhi’s AIIMS visits combined peril with recklessness. After a Sri Lankan soldier struck him with a rifle during a ceremonial parade, X-rays revealed no bone damage. “We sent him home with painkillers,” Bhargava notes. When his son Rahul sustained an arrow graze near his temple, Rajiv tried driving himself to AIIMS to test a vehicle gifted by Jordan’s monarch. Bhargava firmly refused: “You cannot enter my premises driving a car without proper security… dismiss me if you must.” He eventually conceded.

Exposing Healthcare System Corruption

Beyond political conflicts, Bhargava’s memoir provides a devastating critique of India’s healthcare corruption. She mourns the proliferation of kickbacks between general practitioners and specialists – a “cycle of greed” that has “murdered the family doctor.”

Radiologists pay bribes to physicians for patient referrals, inflating diagnostic costs to recoup their illegal payments. “Why be a GP earning peanuts when you can extort as a specialist?” she questioned. Patients suffer misdirection routinely. “A backache patient sees a neurosurgeon, not a GP. The result? Unneeded MRIs, missed kidney issues a tunnel of errors.”

The human toll is devastating. Surgeons experience suicide rates double the general population, yet “pride is a physician’s fatal flaw.” Two AIIMS students died by suicide under academic stress during her tenure. “Resident doctors work 18-hour shifts, eat junk, sleep on stools. We’ve normalised cruelty,” she observed. The COVID-19 pandemic intensified this despair: “COVID broke their spirit. Yet, how many sought help?”

Finding Humanity in Medicine

Despite systemic problems, Bhargava discovered compassionate moments in medical practice. She recalled surgeons visiting temples before challenging operations: “They’d pray harder than the patient’s kin. That’s care.” However, she fears such dedication is disappearing: “Medicine is now tech-savvy but soul-starved. We’re emotionally bankrupt.”

Her modernization efforts at AIIMS met bureaucratic resistance. In the 1970s, officials dismissed her advocacy for CT scanners and ultrasounds, claiming “India is too poor.” Her sharp response: “We buy jets for 300 travellers’ pleasure but deny millions healthcare tech.” These technologies later transformed medical diagnostics. “Technology bridges urban-rural chasms,” she maintained, promoting AI and telemedicine to address India’s radiologist deficit.

Overcoming Internal Sabotage

Bhargava also faced institutional undermining. Dr Lalit Prakash Agarwal, a former dean, became destructive in the 1970s, hampering progress and attacking colleagues. “He stirred envy, digging for dirt in well-run departments,” she wrote. Indira Gandhi finally removed him in 1980 after discovering the organizational turmoil.

Housing shortages presented another significant challenge. The AIIMS campus, designed for fewer staff members, was severely overcrowded. Bhargava advocated relocating slums from hospital property, but bureaucrats obstructed her efforts. Frustrated, she directly confronted Rajiv Gandhi during a public hearing. Her determination succeeded: 50 additional apartments were approved for AIIMS personnel. “Every VIP thought AIIMS was their fiefdom. But patients came first even if it meant staring down a minister,” she writes.

At 95, Bhargava offers a final, candid reflection: “Leadership is a crown of thorns. You bleed, but humility is your shield.” From managing a prime minister’s assassination to fighting corruption and indifference, her narrative exemplifies resilience and integrity.

Her impact continues at AIIMS – an institution serving 1.5 million patients annually – and through her appeal for medicine to reconnect with its humanitarian foundation.

“Where it’s loved, there’s love for people,” she concludes. “Be a healer, not a vendor. Or this noble profession will bleed out.”